STEPBible - Scripture Tools for Every Person - from Tyndale House, Cambridge

__

More about OT Ketiv & Qere

An Explanation of the System of Ketib-Qere (K-Q)

Charles L. Echols, Ph.D.

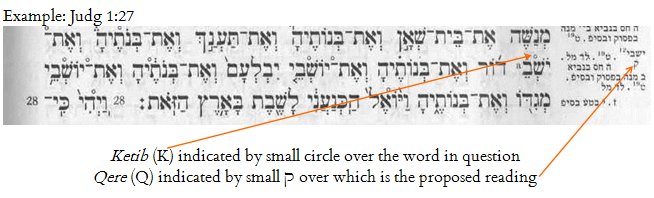

The system of Ketib-Qere was created by the Masoretes to alert the reader to perceived issues with the written text (the Ketib or Ketiv). The Masoretes wrote a small circle over the word in question (the Ketib) that directed the reader to the margin where they wrote a small ק over which they indicated what they believed was the correct reading (the Qere).

Originally Hebrew was written using only consonants. By the Classical period (ca. seventh century BC), terminal vowels were added—but even these were consonants used as vowels. Subsequently, medial vowels were added—again using certain consonants. Not far into the Second Temple Period, Hebrew began to give way to other languages—notably Aramaic and Greek—as the vernacular. Indeed the production of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament), beginning probably in the early third century BC, reflects that fact that Hebrew was no longer the vernacular for most Jews. At least as early as the first century AD, several vowel systems existed to aid in reading Hebrew. The most famous were the Babylonian, Palestinian, and Tiberian systems, in which small marks were added above and below the text. During the rabbinic period, other notations to the text were made (e.g., the division of the text into paragraphs, puncta extraordinaria).

If we speed forward to the ninth-tenth centuries AD, we come to a group of faithful, brilliant Jewish scholars called the Masoretes. They preserved the text that had been passed down to them, including the vowels and notations that accompanied the text. In fact, they compiled further information, including notation on the side margin (the masora parva) and bottom (the masora magna) of each page of the text as well as other information (e.g., the notation between the end of any biblical book and the beginning of the next book). Such was their reverence for the sacred text, however, that they made no alterations to the received consonantal text.

As they made copies of the received text, they noticed occasional differences with how they thought that the received text should be read. They wanted to register the differences and provide what they thought should be the alternative reading; but, again, because the text was Holy writ, they made notes in the margin rather than changing the consonants. The system of Ketib-Qere (K-Q) was implemented by the Masoretes to record such differences. Earlier rabbinic sources indicate that scribes were aware of such differences and had developed alternative readings, but the Masoretes were the first to record them in the margin of the page. [1] The word “Ketib” (“what is written”) is from the Aramaic verb כְּתִיב and refers to the written (consonantal) text. “Qere” (“what is read”) is also Aramaic (קְרַי/קְרִי) and signifies how the Masoretes thought that the text should be read (vocalized).

Some K-Q occur only once or are infrequent. Others, Qere perpetuum (“perpetual” or “constant” Qere) occur regularly as, for example, the Tetragrammaton (יהוה), where the vowels reflect, with some modification, those that belong to אֲדֹנָי. Because perpetual Qeres are invariable the Masoretes did not bother noting them.

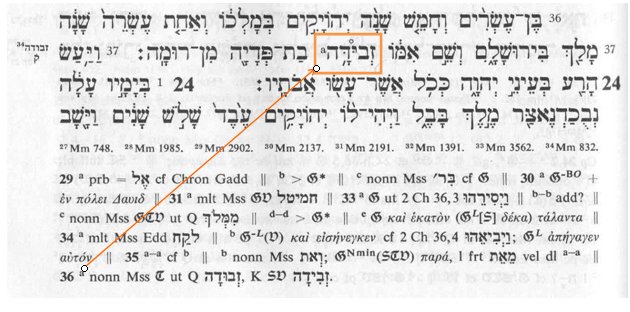

Let’s illustrate the system of K-Q with an example from 2 Kgs 23:36 (on the right)

The Ketib—the proper noun, Zebidah—is enclosed in the box. The small circle over it directs you to the margin where the Qere (זבודה) lies over a small ק. The difference between the Ketib and the Qere is in the third letter, i.e. י (K) and ו (Q). The Masorete scribe pointed the Ketib as he thought it should be vocalized. (Remember that the Masoretes added their system of vowels to the text that was handed down to them.) Hence, one simply transfers the vowels and any dāgēš fortes or lenes from the Ketib to the Qere to see the Masoretic vocalization. Further help comes from the a small, superscript “a” immediately following the Ketib that directs the reader to the critical apparatus at the bottom of the page. There the editor of the apparatus for 1-2 Kings (A. Jepson) provides fuller information. (Not all K-Q are noted in the critical apparatus.) He indicates that several Hebrew manuscripts (nonn Mss) and the Targum () read with (ut) the Qere, while the Syriac and Vulgate () read with the Ketib (as do the NASB, ESV, and NRSV). He also points the Ketib as the Masoretes might have heard it.

Scholars debate over what exactly the Qeres signify, although most work from two general suppositions: the Qeres reflect (a) the majority reading of a number of texts (the “collation” theory) or, (b) an oral correction to a standard text (the “correction” theory). Tov’s recent work expands somewhat in deliberating between three possibilities: the Qeres signify (1) a reading (vocalizing) correction to the Ketib, (2) a written variation from the Ketib, and (3) a reading tradition that accompanied the Ketib.[2] Tov rejects the first opinion because, for example, there are occasions when “the same words . . . sometimes form the Qere word in one verse, and the Ketib word in another one” (p. 57; cf. √אסר, Gen 39:20; Judg 16:21, 25). He debates over the second opinion because “the existence of merely one variant is illogical” (p. 58). Tov is persuaded by the third opinion. As evidence he points to the very terms, Ketib (how the text is written) and Qere (how the text should be read/vocalized). As further evidence that the Qeres are not a record of alternative written readings, he observes (p. 56) that the K-Q are “the only para-textual feature of that is not paralleled by the Judean Desert scrolls,” the latest of which is probably from the 1st century AD. Also, in any given place where the Qere differs from the Ketib, there is only one Qere among all of the manuscripts. Tov (p. 58) allows that there are “intermediate positions” between the three.

In many cases, the third position is the most persuasive; but it is debatable whether it satisfactorily accounts for all of the K-Q. Würthwein, for example, states that the K-Q reflect dissatisfaction with the received text “on grammatical, esthetic, or doctrinal grounds.”[3] Indeed, one cannot be sure that the Qere reading reflects the judgment of the Masoretes on the best of a number of alternative readings as Orlinsky supposed in 1960.[4] Würthwein also registers Gerlemann’s suggestion that in some instances the Qeres record “popular variants.”[5] Elsewhere, even Tov allows that the Qeres perform other functions, instancing √אהל, Gen 9:21, where there is no real aural difference between the Ketib and the Qere.[6]

The example from 2 Kgs 23:36 follows Tov’s opinion that the Qere indicates an alternate vocalization. If the first of the three opinions mentioned above is correct, then the Qere is a correction to the vocalization. If the second is the case, then the Qere reflects an alternate version of the written text.

A few concluding examples will illustrate the variety with which Qeres were used. Some background information is necessary for the first. Since the biblical period spans well over 1000 years, it should not be surprising to find different types of Hebrew. Scholars distinguish between three general types: Archaic, Classical, and Late. Occasionally the Masoretes would “update” instances of Archaic Biblical Hebrew, as is the case in Gen 9:21. The Ketib reads אָהֳלֹה, “his tent,” with the archaic 3ms pronominal suffix ֹה-. “The ה represents the h of the primitive form ahu.”[7] The Qere records the morpheme with the “modern” spelling, i.e., אָהֳלוֹ.

In some places it is quite clear that the text has suffered corruption and the Masoretes would sometime offer a correction. The Ketib for Deut 5:10 (מצותו), for example, reads, “but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep his commandments.” The pronoun “his” is awkward and “my” is clearly wanted, and the Qere supplies it. (It is quite possible that the error came in the process of copying the text as the scribe either mistook י for ו—the two are very similar in handwritten texts—or misunderstood the sound since ay could be aurally close to aw.)

Qeres were also used to harmonize spellings. The example of Oholibama’s first son, Jeush, is an example. The name occurs nine times in the Old Testament: Gen 36:5, 14, 18; 1 Chr 1:35; 7:10; 8:39; 23:10, 11, 19. In seven of these occurrences, the Ketib spells it as יעושׁ, but in Gen 36:5, 14, and 1 Chr 7:10, the Ketib reads יעישׁ. In these three instances, the Qere notes that it should be read as יעושׁ (the majority wins!).

Occasionally the Masoretes saw the Ketib as obscene, blasphemous, or theologically troubling and used the Qere to provide an acceptable reading. In 2 Kgs 18:27, for instance, the Rabshekah delivers an insulting warning to the Israelite soldiers, telling them that they are doomed:

“to eat their own dung (חֲרֵיהֶם) and to drink their own urine (שֵׁינֵהֶם)” (ESV).

The Qere reads:

“to eat their own filth (צוֹאָתָם) and to drink the water of their legs (מֵימֵי רַגְלֵיהֶם).”

The Qere thus substitutes euphemisms for the obscene terms.

The system of K-Q is complex and it origins remain poorly understood. The opinion of Graves has much to recommend it:

Perhaps the immediate origin of the Ketiv-Qere system was the need to record both an authoritative written text and a separate reading tradition, but the ultimate source of the reading tradition was a popular manuscript recension. This would account for both the presence of Qere readings in ancient sources and the function which the Ketiv-Qere system seems to have performed during the Masoretic period.[8]

That said, the uncertainty over the origins of the K-Q has consequences for adjudicating over K-Q divergence. It is probably safe to say that in the majority of cases, the Qere indicates the preferred reading, but there are exceptions as we have seen. Uncertainty over the origins of the system and inconsistencies in its application in preempts any claim to a “one size fits all” approach. Rather, when working through a K-Q, one should consider the different possible explanations and conclude for the one that is the most contextually persuasive.

Nedarim 37b-38a

Although technically not K-Q, there are other Masoretic notations that function similarly. The Babylonian Talmud tractate Ned. 37b-38a, for example, mentions a list of words that are not in the text but that the scribes thought should be, and a list of words that are in the text that the scribes thought should not be (see more here).

[1] That the system of K-Q is a product of the Masoretes is inferred from the fact that none of the ancient manuscripts, particularly those from the Judean Desert, have Qeres (Emmanuel Tov, Hebrew Bible, Greek Bible and Qumran: Collected Essays [Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism 121; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008], 2-3). As evidence that the practice of alternative readings was in place prior to the Masoretes, Tov (p. 6) cites b. Erub. 26a: “It [העיר, 2 Kgs 20:4] is written ‘the city,’ but we read ‘court.’”

[2] Emmanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible (3rd, revised ed.; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2012), 54-59. Compare, in English, where, for example, the vowel “a” in the word “rather” when spoken with a British accent sounds long (as in “alternate”) whereas it is short with a North American accent (as in “bat”). For a survey of explanations of the Qere from ancient to modern times, see Michael Graves, “The Origins of Ketiv-Qere Readings,” Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion; n.p.; accessed 22 November 2013. Online: http://rosetta.reltech.org/TC/vol08/Graves2003.html#fnref1.

[3] E. Würthwein, The Text of the Old Testament (2nd ed.; trans. Erroll F. Rhodes; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 16.

[4] H. M. Orlinsky, “The Origin of the Kethib-Qere System: A New Approach” (Congress Volume; VTSup 7 [1960]), 187, in Graves, “Origins of Ketiv-Qere Readings.”

[5] Würthwein, Text of the Old Testament, 17, n. 21, citing G. Gerlemann, Synoptic Studies in the Old Testament (Lund: Gleerup, 1948).

[6] Tov, Hebrew Bible, Greek Bible and Qumran, 5, n. 17.

[7] Paul Joüon and T. Muraoka, A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew (Revised English ed.; SubBi 27; Roma: Pontifico Istituto Biblico, 2006), §94h.

[8] Graves, “Origins of Ketiv-Qere Readings.”

www.STEPBible.org is created and supported by Bible scholars at Tyndale House, Cambridge

with a great deal of help from volunteers and partnering by many organisations.